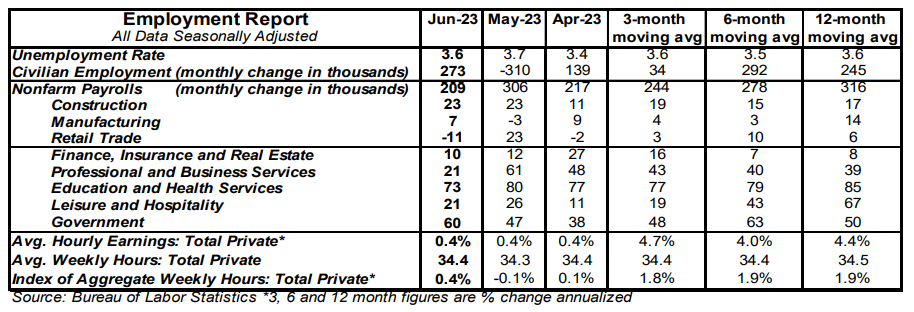

- Nonfarm payrolls increased 209,000 in June, narrowly lagging the consensus expected 230,000. Payroll gains for April and May were revised down by a total of 110,000, bringing the net gain, including revisions, to 99,000.

- Private sector payrolls rose 149,000 in June and were revised down by 98,000 in prior months. The largest increases in June were for education & health services (+73,000), construction (+23,000), professional & business services (+21,000, including temps), and leisure & hospitality (+21,000). Manufacturing increased 7,000 while government rose 60,000.

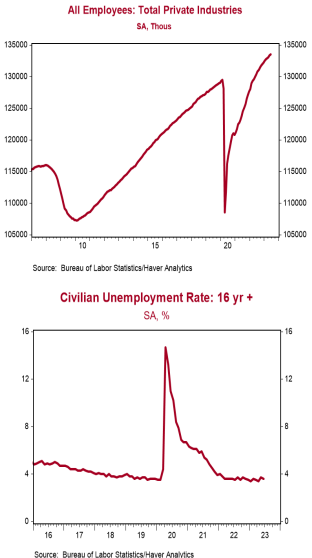

- The unemployment rate ticked down to 3.6% in June from 3.7% in May.

- Average hourly earnings – cash earnings, excluding irregular bonuses/commissions and fringe benefits – rose 0.4% in June and are up 4.4% versus a year ago. Aggregate hours also rose 0.4% in June and are up 1.9% from a year ago.

Implications:

A hint of tepidness in the June labor market, but only a hint. Nonfarm payrolls rose 209,000 in June, a little below consensus expectations. Payrolls were also revised down 110,000 in prior months and, including those revisions, the net gain was 99,000, still upward but well slower than the recent pace of payroll gains. We think this is an early sign that the reduction in the M2 measure of money that began last year is starting to gain traction in slowing the economy. However, we also think today’s report makes it very likely that the Federal Reserve raises short-term interest rates again at the next meeting on July 26. Civilian employment, an alternative measure of jobs that includes small-business start-ups, rose 273,000 in June, helping push the unemployment rate down a tick to 3.6%. Average hourly earnings increased 0.4% in June and are up 4.4% in the past year. Total hours worked increased 0.4% in June, as well. The Fed will take all these figures to mean it has more work to do and that means more rate hikes. Many analysts have been focusing lately on what the Labor Department calls a birth/death model, which is an estimate for net job creation at the birth (or death) of new small businesses that aren’t included in the payroll survey because it is only a sample of existing businesses. In the past twelve months, the birth/death model accounts for 1.4 million of the total 3.8 million increase in payrolls. That may sound like a lot, but it is well within historical norms. In addition, COVID affected small businesses dramatically. Still, it may be that this adjustment is too high. After all, the total payroll gain of 3.8 million in the past twelve months is significantly above the 2.9 million in the household survey (which doesn’t need a birth/death adjustment because the survey is answered by households, whether they have a job at a new company or an old company). Note that the birth/death model only added 26,000 to payrolls in June itself, well below the average of the past year. Ultimately, the Fed wants to see either a big drop in inflation or a substantial worsening in the labor market before it can relent. We don’t think the inflation figures will improve fast enough for the Fed, which means it will feel pressure to maintain a tight enough monetary policy until it sees unemployment heading up while payrolls are heading down.