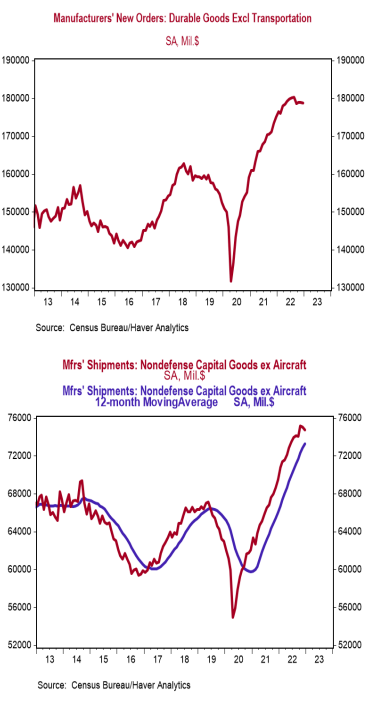

- New orders for durable goods rose 5.6% in December (+6.1% including revisions to prior months), easily beating the consensus expected +2.5%. Orders excluding transportation declined 0.1% in December (-0.2% including revisions), versus a consensus expected -0.2%. Orders are up 11.9% from a year ago, while orders excluding transportation are up 2.1%.

- A surge in orders for commercial aircraft in December was partially offset by declining orders for machinery, computers and electronic products, and primary metals.

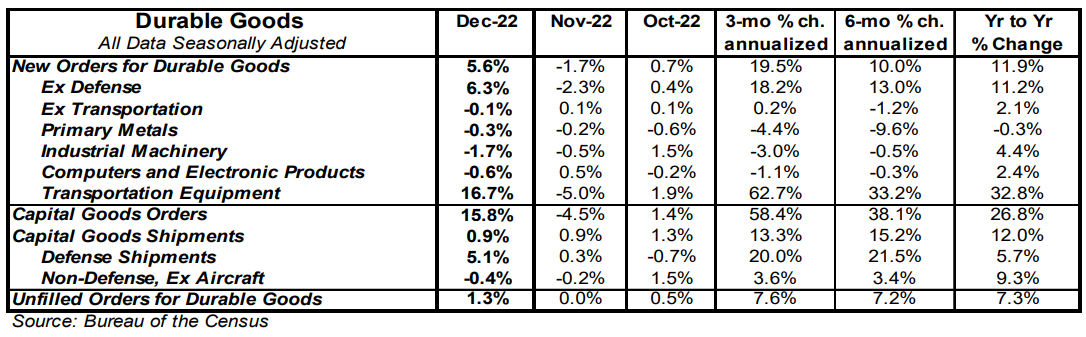

- The government calculates business investment for GDP purposes by using shipments of non-defense capital goods excluding aircraft. That measure declined 0.4% in December but was up at a 5.1% annualized rate in Q4 versus the Q3 average.

- Unfilled orders rose 1.3% in December and are up 7.3% in the past year.

Implications:

New orders for durable goods rose 5.6% in December, easily beating consensus expectations, while previous months were revised higher. But don’t let that headline number fool you; the surge in new orders was due to the volatile commercial aircraft category, which after plummeting 30.7% in November, rebounded 115% in December. Stripping out transportation, orders declined 0.1% in December and were revised lower in previous months. Categories that declined in December include orders for machinery (-1.7%), computers and electronic products (-0.6%), and primary metals (-0.3%). One of the most important pieces of today’s report, shipments of “core” non-defense capital goods ex-aircraft (a key input for business investment in the calculation of GDP), declined 0.4% in December. Despite the drop, these shipments were up at a 5.1% annualized rate in Q4 versus the Q3 average, which provided a (temporary) tailwind for fourth quarter GDP. Orders for core capital goods (which will lead to shipments in the future) showed weakness in December, declining 0.2%. The shift from services to goods accelerated overall durable goods purchases beyond where they would have been had COVID never happened. The return toward services means a large portion of goods-related activity will soften in the year ahead, even as some durables that facilitate services (like airplanes) recover. In other recent news the Federal Reserve reported that the M2 measure of the money supply fell for a fifth consecutive month, down 0.7% in December, the largest monthly decline in more than sixty years. Following the 40.3% explosion in M2 in 2020-21, as stimulus flooded the system, M2 declined 1.3% in calendar year 2022. While that may sound like a modest decline, it’s the largest twelve-month contraction since the 1930s. If the recent data are accurate (we have some doubt) and if this pace continues for a prolonged period, the economy is in for a very rough time in 2023-24 and inflation, which should remain elevated in 2023, could plummet in 2024. On the manufacturing front, the Richmond Fed index, a measure of mid-Atlantic factory sentiment, dropped to -11 in January from 1 in December, the lowest level since the early months of COVID. Finally, initial unemployment claims fell 6,000 last week to 186,000, while continuing claims rose 20,000 to 1.675 million. These data suggest the labor market remains strong, but remember that it will be a lagging indicator of the oncoming recession.