Visualizing the Commodity Super Cycle

Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the world has seen its population and the need for natural resources boom.

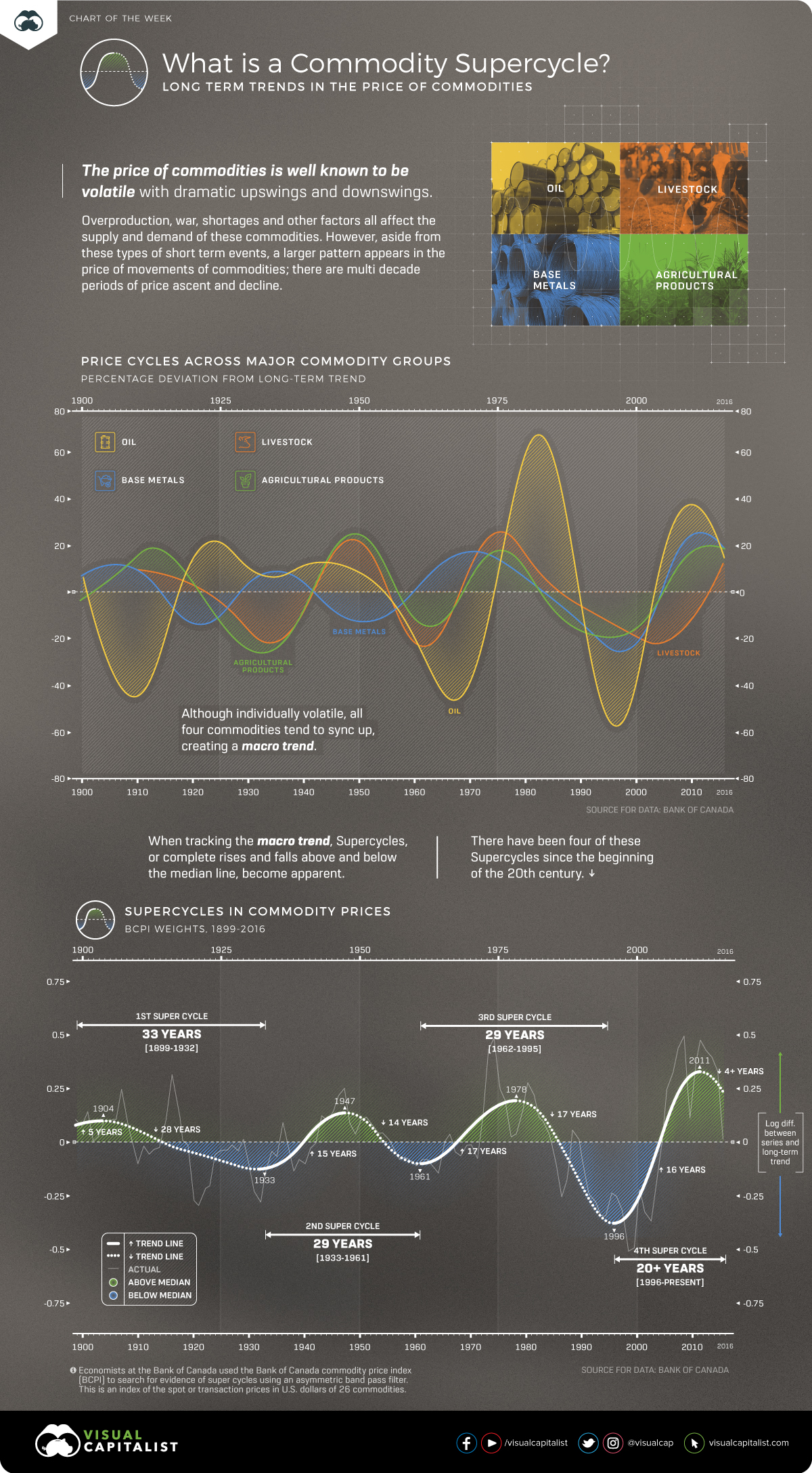

As more people and wealth translate into the demand for global goods, the prices of commodities—such as energy, agriculture, livestock, and metals—have often followed in sync.

This cycle, which tends to coincide with extended periods of industrialization and modernization, helps in telling a story of human development.

Why are Commodity Prices Cyclical?

Commodity prices go through extended periods during which prices are well above or below their long-term price trend. There are two types of swings in commodity prices: upswings and downswings.

Many economists believe that the upswing phase in super cycles results from a lag between unexpected, persistent, and positive trends to support commodity demand with slow-moving supply, such as the building of a new mine or planting a new crop. Eventually, as adequate supply becomes available and demand growth slows, the cycle enters a downswing phase.

While individual commodity groups have their own price patterns, when charted together they form extended periods of price trends known as “Commodity Super Cycles” where there is a recognizable pattern across major commodity groups.

How can a Commodity Super Cycle be Identified?

Commodity super cycles are different from immediate supply disruptions; high or low prices persist over time.

In our above chart, we used data from the Bank of Canada, who leveraged a statistical technique called an asymmetric band pass filter. This is a calculation that can identify the patterns or frequencies of events in sets of data.

Economists at the Bank of Canada employed this technique using their Commodity Price Index (BCPI) to search for evidence of super cycles. This is an index of the spot or transaction prices in U.S. dollars of 26 commodities produced in Canada and sold to world markets.

- Energy: Coal, Oil, Natural Gas

- Metals and Minerals: Gold, Silver, Nickel, Copper, Aluminum, Zinc, Potash, Lead, Iron

- Forestry: Pulp, Lumber, Newsprint

- Agriculture: Potatoes, Cattle, Hogs, Wheat, Barley, Canola, Corn

- Fisheries: Finfish, Shellfish

Using the band pass filter and the BCPI data, the chart indicates that there are four distinct commodity price super cycles since 1899.

- 1899-1932:

The first cycle coincides with the industrialization of the United States in the late 19th century. - 1933-1961:

The second began with the onset of global rearmament before the Second World War in the 1930s. - 1962-1995:

The third began with the reindustrialization of Europe and Japan in the late 1950s and early 1960s. - 1996 – Present:

The fourth began in the mid to late 1990s with the rapid industrialization of China

What Causes Commodity Cycles?

The rapid industrialization and growth of a nation or region are the main drivers of these commodity super cycles.

From the rapid industrialization of America emerging as a world power at the beginning of the 20th century, to the ascent of China at the beginning of the 21st century, these historical periods of growth and industrialization drive new demand for commodities.

Because there is often a lag in supply coming online, prices have nowhere to go but above long-term trend lines. Then, prices cannot subside until supply is overshot, or growth slows down.

Is This the Beginning of a New Super Cycle?

The evidence suggests that human industrialization drives commodity prices into cycles. However, past growth was asymmetric around the world with different countries taking the lion’s share of commodities at different times.

With more and more parts of the world experiencing growth simultaneously, demand for commodities is not isolated to a few nations.

Confined to Earth, we could possibly be entering an era where commodities could perpetually be scarce and valuable, breaking the cycles and giving power to nations with the greatest access to resources.

Each commodity has its own story, but together, they show the arc of human development.

By Nicholas LePan

August 2, 2019